Deadlock¶

Deadlock - definition¶

Formal: A condition when two or more threads of execution are each waiting for resources in a cycle.

Informal: When two threads get into a chicken before the egg situation in locking.

When a deadlock condition occurs, unless otherwise broken, the threads of execution involved will remain halted until they are terminated externally.

If deadlock is possible, it may not always happen immediately. If it is possible it can happen eventually given the right timing.

Dining Philosophers Problem¶

a philosopher can be either eating or thinking

philosophers cannot communicate with each other in any way

to eat, a philosopher needs both the right and left fork

Dining Philosophers - deadlock scenario¶

eat() {

pick up right fork;

pick up left fork;

proceed with eating;

}

t = 0: p1, p2, p3, p4, p5 each pick up right fork

t = 1: p1 tries to pick up left fork, cannot proceed because p5 has it held

t = 2: p2 tries to pick up left fork, cannot proceed because p1 has it held

t = ……

The waiting operation will continue forever. Each philosopher has one fork in their hand. Each philosopher is waiting on a fork held by another

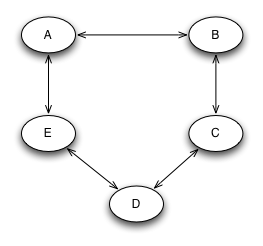

Dining Philosophers - Lock Graph¶

In the first algorithm, locks can be obtained in any order. Given this, it is possible to draw a cycle on the graph and deadlock.

Dining Philosophers¶

What algorithm can we implement for eat() so that there will be no deadlock?

Why did we encounter deadlock?

Dining Philosophers - solution 1¶

eat() {

while(does not have both forks) {

pickup left fork

if(can pick up right fork) {

pick up right fork;

} else {

put down left fork;

}

}

proceed with eating

}

this solution works because it obtains both forks as an atomic operation: if the philosopher cannot obtain the second fork, they put down their held fork. either they get both forks or no forks.

this prevents a cycle because of the check operation

Dining Philosophers - solution 2¶

each fork is assigned a number

eat() {

pick up fork with lower number

pick up fork with higher number

proceed with eating

}

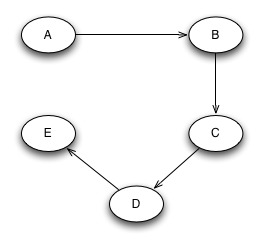

this solution works because the resources are assigned a partial order. this effectively reduces the number of possible edges in the order of locks that can be obtained in the resource lock graph. the graph is reduced to an directional acyclic graph which by definition cannot have cycles and cannot deadlock.

In solution 2, since the order of locks is agreed upon, the graph becomes directed and acyclic.

Given these rules, you cannot draw a cycle on this graph and cannot deadlock

Dijkstra’s Solution / Bankers Algorithm¶

Solution #2 to the dining philosopher’s problem is also known as Dijkstra’s solution or the banker’s algorithm

- Up sides to this solution

Simple to implement and verify lock ordering.

Multi-lock algorithms can be implemented by comparing memory addresses. i.e. mutexes can be locked in the order they appear in memory

- Down sides to this solution

If you examine the undirected cyclic graph earlier, there are several permutations of acquiring locks that do not deadlock.

In the directed acyclic graph, all permutations are deadlock free, but the total number of deadlock free permutations is much less than in the undirected cyclic graph

Because of these issues, the total concurrency possible is less than optimal

Optimization to Dijkstra’s Solution¶

Solution #1 represents an optimization to Dijkstra’s solution.

In solution #1, the graph remains undirected and cyclic, but the heuristic is changed to only obtain both resources if they can be obtained atomically.

In solution #1, all of the possible deadlock free permutations can be achieved. Because of this, more concurrency is possible.

The downside to solution #1 is that it is typically more complex to implement

Deadlock Avoidance Implementation¶

aka. Banker’s algorithm

aka. Dijkstra’s solution

typedef struct {

int LockNumber;

void* LockObject;

} lock;

void multi_lock(lock* locks, int count) {

sort(locks, count);

for(int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

lock(locks[i]);

}

}

Deadlock Prevention Implementation¶

aka. optimization to Dijkstra’s solution

This is just one implementation approach. Others involving lock tables or coordinators also exist

typedef struct {

int LockNumber;

void* LockObject;

} lock;

void multi_lock(lock* locks, int count) {

while(1) {

int i = 0;

for(i = 0; i < count; i++) {

if(!try_lock(locks[i])) {

for(int j = 0; j < i; j++) {

unlock(locks[j]);

}

break;

}

}

if(i == count) {

return;

}

}

}

Example of Deadlock¶

Where is the Deadlock?

void method1() {

a.lock();

method2();

a.unlock();

}

void method2() {

b.lock();

c.lock();

b.unlock();

c.unlock();

}

void method3() {

c.lock();

method2();

method4();

c.unlock();

}

void method4() {

d.lock();

d.unlock();

}

Multi-Lock Solutions in Windows¶

C++ method in Windows is WaitForMultipleObjects().

The method accepts N many lock handles

- This method accepts many types of resources and locks:

events

mutexes

semaphores

timers

and many others…

Multi-Lock Solutions in Linux/Minix¶

To my knowledge, there are no multi-lock solutions provided for free in Linux or Minix

The general rule of thumb is to try to avoid multi-locking if possible by design or if it is necessary to use the memory order of the locks as an ordering.

If using shared memory semaphores, memory ordering WILL NOT work since virtual addresses will not be reliable. In this case, lock ordering must be enforced by some other mechanism such as storing locks in an array and locking them in the array’s order.

Deadlock with Lock Ordering¶

While having multiple locks obtained out of order can lead to deadlock, it is possible for correctly ordered locks to end up in deadlock in other ways.

- If an executing thread locks a resource and fails to release the lock, any other thread trying to obtain the lock will be deadlock. This can occur for one or more of the following reasons:

Programmer error: there is no call to release a lock

A thread crashes without releasing a lock

The condition for releasing a lock is never met (infinite loop, poorly defined rules in a monitor, etc..)

These types of deadlock are practically more difficult to handle.

Starvation¶

Starvation is a close cousin to deadlock. Starvation means that practically, one thread will have exclusive lock on a resource and one or more threads will not.

This is similar to a scheduling problem in terms of fairness.

Example live lock problem:

Thread1:

Queue _queue = new Queue();

Mutex _mutex = new Mutex();

void add() {

int value = 0;

while(1) {

_mutex-»Lock();

while(_queue-»count() » 0) {

value += _queue-»Dequeue();

printf("current value = %d\n", value);

}

_mutex-»Unlock();

}

}

Thread2:

void read_values() {

while(1) {

int value = 0;

_mutex-»Lock();

scanf("%d\n", &value);

_queue-»Enqueue(value);

_mutex-»Unlock();

}

}

There are two potential starvation problems here. Can you spot them?

In thread1, we make a call to printf(). This will cause thread1 to go to sleep at which time, thread2 will not be able to obtain the lock.

In thread2, we make a call to scanf(), while waiting for input the lock is held and thread1 will not be able to acquire the lock

How can we make this code better?

Thread1:

Queue _queue = new Queue();

Mutex _mutex = new Mutex();

void add() {

int value = 0;

while(1) {

_mutex-»Lock();

while(_queue-»count() » 0) {

value += _queue-»Dequeue();

_mutex->Unlock();

printf("current value = %d\n", value);

_mutex->Lock();

}

_mutex-»Unlock();

}

}

Thread2:

void read_values() {

while(1) {

int value = 0;

scanf("%d\n", &value);

_mutex-»Lock();

_queue-»Enqueue(value);

_mutex-»Unlock();

}

}

In this version of the code, the locks are not held during I/O operations like printf or scanf (which call read and write).

Because locks are not held during blocking operations, locks and unlocks will occur more often which will reduce the average waiting time to receive a lock.

Guidlines to Avoid Starvation¶

Where possible, limit locks to computationally bound code

Keep critical sections short. If a computation is longer running, design code to give up a lock periodically.

- If possible, make copies in critical sections and perform computations outside of locks. An example could be:

acquire lock

copy item in queue

update item as “in progress”

release lock

perform computation

acquire lock

remove item from queue

release lock

Make sure the lock library you use has some fairness guarantee.

Livelock¶

Livelock is similar to deadlock.

Livelock is basically a race condition in avoidance of deadlock.

An example of livelock would be if one process is trying to multi-lock by testing, then acquiring each lock in turn, and another process is doing the same, they could both block each other by their corrective actions.

Example:

void thread1() {

while(1) {

a.lock();

if(b.trylock()) {

//do work

b.unlock();

}

a.unlock();

}

}

void thread2() {

while(1) {

b.lock();

if(a.trylock()) {

//do work

a.unlock();

}

b.unlock();

}

}

t0: thread1 locks a, context switch

t1: thread2 locks b, tries to lock a, fails, context switch

t2: thread1 tries to lock b, fails, unlocks a, context switch

t3: thread 2 unlocks b, context switch

Lock Fairness¶

Lock fairness is best described as having each executing thread waiting for a lock having a similar average wait time for that lock.

Locks that are unfair can lead to resource starvation.

- The two most common approaches involve:

FIFO queues - common

Lock scheduler with a time table and history - not common

Lock Fairness. Pros / Cons¶

Remember, while the word ‘fair’ sounds good, that ‘fairness’ comes at some expense.

The key point to remember, is that when a thread is “chosen” to acquire a lock, there will be a non zero time between that choice and when that thread executes. That can be thought of as the “fairness cost”.

- Pros:

Reduces starvation

Creates more predictable execution patterns

- Cons:

If a thread locks in a loop, letting a thread re-acquire a lock if its quantum isn’t complete can improve total performance. Fair locks don’t always allow for a lock to be re-acquired if the quantum isn’t finished. This can lead to shorter quantums which will hurt throughput.

Lock fairness can create short quantums for short locks. This can in-turn hurt locality